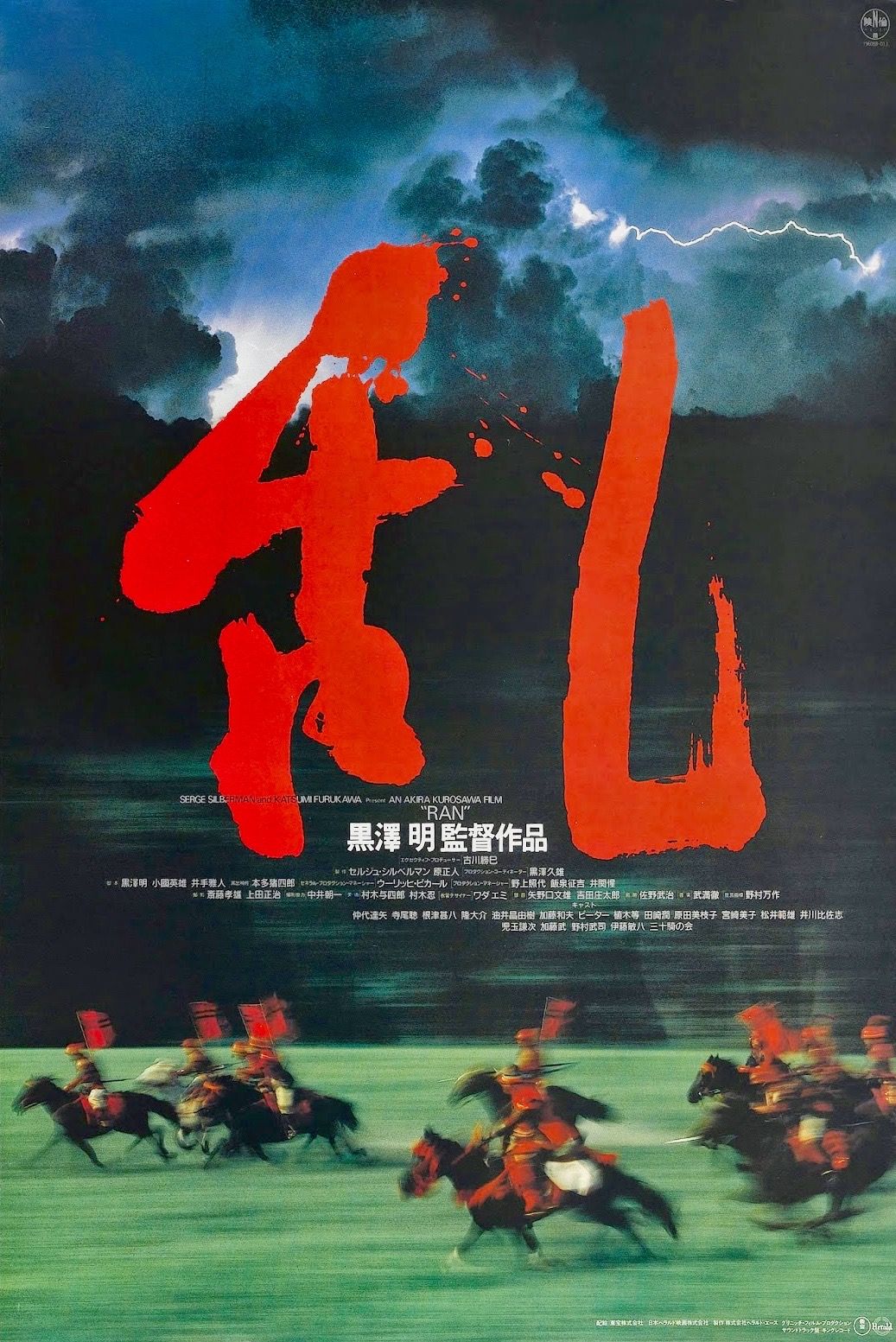

If someone were to ask me which film represents the Sengoku Jidai, I would say that the title goes to Ran. Released in 1985 and directed by Akira Kurosawa, this Shakespearean epic follows Ichimonji Hidetora, a powerful daimyo who decides to leave his clan to his three sons, who ultimately go to war against each other. It is based on King Lear and is considered one of the best films of all time. In this review, we are going to break down some of the key elements of the story and how they reflect the Sengoku Jidai, giving us a glimpse into a world that bred violence and despair.

*Warning: We will be discussing the film in depth, which means that it will contain spoilers. Read at your discretion.

Why Hidetora is familiar to Sengoku historians

While film buffs might recognize the actor, Nakadai Tatsuya, from other samurai films such as Harakiri, historians will pick up on some of the subtle nods to a famous Sengoku figure. The most glaring hint comes from the arrow scene. Hidetora gathers his three sons and explains to them that while one arrow can easily be broken, three arrows together cannot. This scene mimics the story that is attributed to Mōri Motonari (1497-1571). It’s an event that has become legendary, with it being taught in schools today, but that is not the only thing that Hidetora and Motonari have in common.

Before the “arrow lesson”, Hidetora gives us a glimpse of the kind of man he was during his prime and it sounds similar to other daimyō who lived during this age of war. He rose from nothing, fighting his way to the top, then used his influence to annihilate his enemies while also marrying his sons off to their daughters. The similarities do not stop there. Hidetora is wanting to retire; to hand things over to his sons, but it is obvious that he would be the one still running the show as he refuses to part from his retainers and army. This is something that Motonari did himself, as well as Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who though retired, ran the country as if he never did.

The comparisons to Motonari have been confirmed, even by Kurosawa himself, for the whole idea for the film came about after reading the parable. Instead of the parable going well for Hidetora and his sons, Kurosawa wanted to show us, in a fictional setting, what it would look like if the lesson was not learned. Ran gruesomely depicts just that.

Never-Ending Power Struggles

The point of the arrow lesson was to have his sons; Taro, Jiro, and Saburo, work together while their father lived out the rest of his life in retirement. Though Taro and Jiro are on board, Saburo is critical of this move, claiming that they are warriors like their father before them. This scene shows the struggle that samurai of the Sengoku Period dealt with. Peace was hard to obtain, and even then, once established, it meant a significant change in their lives. Most of these men had dealt with the chaos for decades, and as each year passed without resolution, their troubles were pushed onto the next generation. Unfortunately, Saburo is exiled for pointing out the hypocrisy of the situation; that their father, who waged war and mercilessly killed innocent lives to get to where he is today, now wants to live in peace.

The division between the three sons leads to a succession dispute of sorts, something that is almost a hallmark of the samurai era. Taro tries to get his father to renounce his title so that he can take it. Hidetora hopes that Jiro will take him in without issue but again, is met with a problem there. His attempt to unify them brought about further division. Though their father is still alive, brother turns against brother, fighting for the title of clan head. The Sengoku Period is littered with these events, starting with the succession dispute within the Ashikaga that led to the Ōnin War, Oda Nobunaga going to war against his younger brother, Oda Nobuyuki, and even the Uesugi nearly collapsed due to a civil war that broke out after Uesugi Kenshin’s death. As the film goes on, we see how the clan deteriorates because of Taro and Jiro’s greed and Hidetora’s unwillingness to relinquish his title.

Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned

While the focus of the film is on Hidetora and his sons, there are two women that play an important role in the film, one more so than the other. The wives of Taro and Jiro are both victims of Hidetora’s rampages during his prime, yet both are in stark contrast to one another. The first we meet is Taro’s wife, Lady Kaede. Audiences learn right away that she is the one that controls that household, convincing her husband that the title of clan head should be his and that Hidetora should relinquish it. We later learn of her past and that the castle they now occupy once belonged to her family. She starts targeting Jiro after the death of her husband, leaning into his desire for power and using sex as a weapon. This is all a part of her plan to finally avenge her family by bringing down the Ichimonji clan from within. Unfortunately, Lady Kaede is a representation on why women during this era were never trusted. Depending on their circumstances, these women would have secret missions bestowed to them by family, or even have their own agendas, which could lead to the downfall of a clan if men were not careful. While this was not all women, men had to especially be careful if they were marrying someone from a clan that was once their enemy. The most famous example of this is Oda Nobunaga’s marriage to Nōhime. Rumors state that she was married off to Nobunaga to assassinate him, but sources struggle to confirm these claims.

Lady Sue, Jiro’s wife, is the opposite of Lady Kaede and her character is impressive in a completely different way. Like Lady Kaede, she too has lost her family to Hidetora, except for her brother, Tsurumaru. Instead of giving into the hate that drives Lady Kaede to bring down the house of Ichimonji, Lady Sue turns to the Buddha and forgives Hidetora for the annelation of her family. This is something that disturbs Hidetora when he comes to visit his second son. He is used to hatred, making him fearful of Lady Sue’s forgiveness. Perhaps this is her own way of getting revenge by killing him with kindness.

The Role of the Fool

Another aspect of warrior life appears in this film, yet it is not explicit. A good number of Shakespeare’s tragedies have a comic relief character, to help bring some humor to a script that deals with some heavy material. King Lear, the play in which Ran is heavily influenced by, contains a character known only as the Fool. While there is not an equivalent in Japanese society from the era depicted in the film, the character Kyoami, takes on a role that might be familiar to those that know their history well. We have talked about wakashudō on the website before, an apprenticeship of sorts that contains an element of homosexuality, and Kyoami, portrayed by Peter, is an example of such a relationship. Though Kyoami is older than those who would participate in this practice, we get hints about the depth of his relationship with Hidetora. Much of this comes out during the scenes at the castle ruins. Kyoami talks mainly to himself, but it is directed at Hidetora, about how he used to take care of him. Again, while it is not in your face about its implications, the character’s youthful appearance, hairstyle, and closeness to Hidetora point to the two having such a relationship. This was normal for the times, with the most famous case being the relationship between Mori Ranmaru and Oda Nobunaga.

Ran Overall

There is a good reason why I hold this film in such high regard. It perfectly embodies the hell that was the Sengoku Jidai. Family members could not even trust one another, constantly bringing Japan back into the cycle of chaos. It is also hauntingly beautiful. From the eerie soundtrack to using nature as a mood indicator, Ran portrays the emotions of each scene well. It is a colorful film despite its content, something that is lacking in modern films and television shows today. Very few special effects were used; one of the exceptions being the burning of the First Castle, which was filmed at the historic Himeji Castle. The burning of the Third Castle was a set located near Mount Fuji and was done in one take. We are also treated to one of Kurosawa’s famous battle sequences with a segment that is similar to one of his older films, Kagemusha. The whole thing ends with an all is lost moment that leaves you hollow.

Ran is a 10/10 film for me because of two things. First, it is a perfect representation of the Sengoku Jidai. Secondly, it does King Lear better than the original source material, at least in my opinion. Lear seems to suffer needlessly, but Hidetora is being repaid for the horrors he committed during his rise to power, yet because of his past actions, the suffering continues. It is a dark tale with a colorful palette and honestly, one of the best films ever made.

Ran is available to purchase on Amazon (DVD or digital) or through AMC.